Croatian

Language Chronology

Pronunciation

basics:

Č,

č-as the "ch" in "check

Ć,

ć-no English equivalent. Place the tip of the tongue behind the

lower front teeth and try to produce a "mixed sound" between the

"ch" of "check" and the "t" (actually "ty") of British English

"tune". As it were, a “soft” č.

DŽ,

dž-as the "j" in English "jar"

Đ,

đ-no English equivalent. Place the tip of the tongue behind the

lower front teeth and try to produce a "mixed sound" between the

"j" of "jar" and the "d" (actually "dy") of British English "duke".

A “soft” dž.

LJ,

lj-as the British English pronunciation of the "lli" in "million",

i.e., with a "clear 'l'" followed by a short "y"-sound

NJ,

nj-as the "ni" in "onion", i.e., an "n" followed by a short "y"-sound

Š,

š-as the "sh" in English "ship"

Ž,

ž-as the "s" in "measure" or the "zh" in "Zhivago"

Nota

bene:

Č,č-ch

Š,š-sh

Ž,ž-zh

Croatian

Language Chronology

Summary

Pre-history

Indo-European

and Slavic languages

-

2000 B.C.E.- the formation of Balto-Slavic linguistic family.

-

1500-1300 B.C.E. -disintegration of Balto-Slavic family followed

by numerous languages changes characteristic for shape of

future Slavic languages. The basic features of this period

can be only approximately reconstructed by methods of comparative

historical linguistics.

-

4th

-8th centuries- migrations of Slavic-speaking tribes

that will definitely divide Slavic languages into three groups:

eastern (Russian, White-Russian, Ukrainian, Ruthenian), western

(Polish, Kashubian, Lower Sorabian, Upper Sorabian, Czech,

Slovak) and southern (Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian,

Macedonian, Bulgarian, Church Slavonic).

600

to 1100

Latin

and Church Slavonic literacy

Glagolitic

Script as the medium of Croatian Church Slavonic

-

7th

to 9th century. First Croatian “official”

language was Latin and Croatian name is recorded in Latin

inscriptions of Croatian rulers (dukes and kings) in the 9th

century.

Duke

Branimir inscription, ca. 880

The

earliest Croatian Dukes and Kings

THE MUSEUM OF CROATIAN

ARCHEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS

- 9th

to 11th centuries: the dominance of Church Slavonic,

first literary language of all Slavs, based on a south Macedonian

dialect. In time, variants of Church Slavonic emerge (Croatian,

Russian, Czech, Serbian, Bulgarian), as a result of intrusion

of the vernacular. First Croatian script, Glagolitic, was

probably invented by missionaries from Thessalonica Cyril and

Methodius (ca. 850), whose disciples, expelled from Moravia (contemporary

Slovakia and Czech Republic), settled in Croatian lands. The originally

“round” form of Glagolitic script soon becomes angular- the distinct

feature of Croatian Glagolitic. Historicallly, the most important

monument of early Croatian literacy is the Baška tablet

(ca. 1100).

The

Baška tablet, ca. 1100

THE

BASKA TABLET

precious stone of Croatian literacy

Croatian

Glagolitic Script

Old

Church Slavonic Institute

1100

to 1500

Church

Slavonic literature, dialectal differentiation and vernacular

literacy

Cyrillic and Latin Script

-

However, the luxurious and ornate representative texts of Croatian

Church Slavonic belong to the later era when they coexisted

with the Croatian vernacular literature. The most notable are

the Missal of Duke Novak from Lika region in northwestern

Croatia (1368), Evangel from Reims (1395, named after

the town of its final destination), Missal of Duke Hrvoje

from Bosnia and Split in Dalmatia (1404) and the first printed

book in Croatian language (1483). Great migrations following

the Ottoman invasion, the growing influence of Croatian or

Bosnian Cyrillic and, finally, the prevalence of Latin script

-both as the medium of western literature (sacral and secular)

and the dominant, although not standardized Croatian script-

all these factors spelled the doom of Glagolitic literacy. Croatian

Glagolitic scriptory tradition died out, mainly, in the 17th

century.

Evangel

from Reims, 1395

The

Missal of Duke Hrvoje, 1404

Missale

Hervoiae ducis Spalatensis Croatico-Glagoliticum

Croatian

Glagolitic Manuscripts held outside of Croatia

-

12th-15th centuries: the period of dialectal differentiation.

Croatian dialects are, roughly, divided in three groups named

after the dialectal word for interrogatory pronoun which is

in Latin «quid» or in English «what»: ča-Čakavian

(chakavian), što-Štokavian (shtokavian) and

kaj-Kajkavian (kaykavian). These dialects and

their subdialects have undergone further changes in next 5 centuries,

but the central characteristics were virtually fixed by the

17th century. Phonetic, phonological and morphological differences

between dialects vary from 4 to ca. 30 characteristic features,

as does mutual intelligibility between both dialects and subdialects.

Štokavian dialect was further divided into western branch (3

accents speech), spoken mainly by Croats, and eastern ( 2 accents

speech), spoken predominantly by Serbs. Kajkavian was spoken

in northwestern Croatia, Čakavian in western Croatia and Dalmatia

(littoral, islands and hinterland), and western Štokavian in

the northern Croatia/Slavonia, as well as in the greater

part of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the esternmost part of Bosnia

and Herzegovina was the area of eastern Štokavian dialect).

-

Another differentiating feature was the result of phonetic development

of Old Slavonic phoneme ě (jat). For instance,

Church Slavonic word for a child, děte, became in three

“jat reflexes”:

-dite

(i, hence Ikavian)

-dijete

(ije, hence Ijekavian)

-dete

(e, hence Ekavian)

These

features are most prominent in Štokavian dialect (što-i,

što-ije and što-e), but are present in other Croatian

dialects (ča-i, ča-ije, kaj-e). The most widespread Croatian

dialects, from 1400s on, have been Štokavian Ikavian and Ijekavian

(što-i and što-ije), but other dialects, especially

Čakavian (ča-i) and Kajkavian (kaj-e) played the

prominent role (Čakavian influence dimmed in 17th century, and

Kajkavian was consciously abandoned in 1830s by Illyrian

movement that completed Croatian language unification by

«officially» accepting neo-Štokavian dialect (a variant

of Štokavian originating from the Neretva river basin in Herzegovina

ca. 1500) as the basis of the Croatian standard language

since it was the speech of more than 70% of the Croats and the

dialect of the richest Croatian literature in past 350 years.

Neo-Štokavian differs from older variants of Štokavian by 4

accents speech and a few (3-6) morphological structural changes.)

-

To complicate the situation further, this was the period when

other scripts appeared and became influential on Croatian soil:

Cyrillic («Povaljska listina»/The Povlja lintel, 1184),

which soon adopted specific scriptory and morphological characteristics

that made it different from other (Serbian and Bulgarian) versions

of the Cyrillic, and Latin (ca. 1350). The Croatian (or

Bosnian, since it was dominant in medieval Bosnia-hence the name

«bosančica»/Bosnian script) Cyrillic was influential in

parts of central and south Dalmatia, as well as in Bosnia, where

it had been most widely used from 14th to 17th century; the Latin

script gained ground in Croatian regions with most vigorous economic

and cultural activity (Dalmatian littoral, northern Croatia) and

by 1500s it was evident it will prevail at the end.

Croatian

Cyrillic Script

Croatian

Heritage in Latin Script

-

First

texts in purely vernacular language are: «Vinodolski zakon»/The

Vinodol Codex (1288), «Istarski razvod»/Istrian land survey

(1325) and «Šibenska molitva»/The prayer to Our Lady (ca. 1350)-

all in Čakavian dialect; «Vatikanski hrvatski molitvenik»/The

Vatican Croatian Prayer Book (ca. 1380-1400) in Štokavian-Ijekavian

dialect. Kajkavian literature is much younger-it begins

at the end of 16th century.

The

Vinodol Codex, 1288

The

Vatican Croatian Prayer Book, Dubrovnik, ca. 1380-1400

1500

to 1700

Modern

Croatian language

Turkish invasion and migrations Renaissance

and Baroque regional literatures and standardization

-

During

16th and 17th centuries occurred many

processes that shaped the profile of future Croatian standard

language: the Ottoman invasion and permanent warfare, followed

by mass depopulation and migrations have had at least four

lasting consequences:

-

the area of Čakavian, the oldest Croatian dialect was

greatly narrowed. Although the Renaissance literature in Čakavian

vernacular achieved remarkable triumphs (epic and lyric poetry,

novel) in the 16th century (especially on islands

Hvar and Korčula and cities Split and Zadar, with key authors

like Marko Marulić, Hanibal Lucić and Petar

Zoranić), its demographic and cultural basis had soon

become exhausted and Čakavian lost the chance to become the

basis of Croatian national language.

-

Turkish

conquests have been followed by migrations of Vlachs- mainly

Slavicized shepherding paleo-Balkans populace from earlier

conquered areas in Albania, Serbia, Montenegro and Herzegovina.

The result was expansion of neo-Štokavian dialect in Ikavian

(što-i) and Ijekavian (što-ije) forms. The majority

of settlers later nationally identified according to the faith

they professed: the Eastern Orthodox Vlachs became Serbs and

Roman Catholics became Croats.

-

The

literature and lexicography in Kajkavian dialect appeared

on the scene, but the most influential and promising was the

literature in Čakavian-Kajkavian-Štokavian interdialect, based

in central Croatia and supported by powerful Croatian nobles

Zrinski and Frankopan (both writers themselves).

However, this extraordinary activity that produced at least

two major figures: polymath, forerunner of modern Croatian

national ideology and script reformer Pavao Ritter-Vitezović

and lexicographer Ivan Belostenec (his

magnum opus, the 2,000 pages long Kajkavian-based interdialectal

dictionary “Gazophylacium” (ca. 1670) was published some 60

years after its completion) was cut short by execution of

Zrinski and Frankopan in Bečko Novo Mesto 1671,

after a kangaroo trial orchestrated by the Vienna court-leaving

Croatia literally decapitated for a time. The Kajkavian-based

interdialect later flourished in north-western Croatia (in

and around Zagreb), but was essentially confined to

a corner of Croatian language area and could not become transregional

Croatian koine.

Ivan

Belostenec: Gazophylacium, 1740

-

the

extraordinary flourishing and continuous influence of the

southern Croatian Renaissance literature in Dalmatia, with

centres in cities like Split, Zadar and Dubrovnik, or islands

Korčula and Hvar, laid the foundation for the idiom that was

to became the basis of Croatian standard language. At first,

it was written in Čakavian and Štokavian dialects

(with strong dialectal interference, so that many features

of Čakavian can be found in Štokavian and vice

versa), but soon, after the depopulation and economic and

cultural marginalization of other Dalmatian towns, the Dubrovnik

writers, who wrote in increasingly unidialectal Štokavian-Ijekavian,

remained alone on the scene. The key authors are poets Šiško

and Vladislav Menčetić, Dominko Zlatarić, numerous

poets from Ranjina's collection of sonnets and the

dramatist Marin Držić.

Ranjina's

collection of poems, 1508

A

COMPENDIUM OF CROATIAN LITERARY RESOURCES ON THE WEB

A

digital collection of poetry dating from the Renaissance to

the end of the 19th century

¦

What the Renaissance writers accomplished in the 16th

century had been further developed and refined in the 17th.

This period, sometimes called Baroque

Slavism was crucial in formation of literary idiom that

was to become Croatian standard

language: the 17th century witnessed luxuriance

in three fields that shaped modern Croatian:

?

The first one was represented by the linguistic

works of Jesuit

philologists Kašić and Mikalja: the first Croatian

grammar,

authored by Bartol Kašić under the title: “Institutionum

linguae illyricae libri duo”, appeared in Rome 1604.

Interestingly enough, the language of Jesuit Kašić's unpublished

(until 2000) translation of the Bible

(Old and New Testament, 1622-1636)

in the Croatian Štokavian-Ijekavian dialect (the ornate

style of the Dubrovnik

Renaissance literature) is as close to the contemporary standard

Croatian language (problems of orthography

apart) as are French of Montaigne's

“Essays” or King James Bible

English to their respective successors - modern standard languages.

The richness of Kašić's translation can be seen in the

vocabulary: while the original Old Testament consists of 8,674

Hebrew words, and New Testament of 5,624 Greek words, the vocabulary

of Kašić's Bible translation numbers near 20,000

words. However, Kašić's most influential book was “Ritual

Rimski”/The Roman Ritual, a liturgical compendium that had been

in use from 1640 to 1929 and has decisevely shaped the profile

of Croatian language; Mikalja's “Thesaurus linguae Illyricae”

was first respectable (25,000 Croatian entries) dictionary of

Croatian language mainly in Štokavian-Ijekavian idiom.

Bartol

Kašić: Ritual Rimski/Roman Ritual, 1640

Mikalja:

Blago jezika slovinskoga/Treasure of Illyrian language, Loreto

1649

-

another

strong influence was the energetic literary activity of

Bosnian Franciscan Matija

Divković, whose Counter-Reformation

writings (popular tales from the Bible,

sermons and polemics) were widespread among Croats

both in Bosnia

and Herzegovina and Croatia

and played the crucial role in preserving and forging the

cultural and linguistic unity among Croatian common people

who lived in two empires: Ottoman and Habsburg.

Matija

Divković: Besjede/Orations, 1616

-

and, last but not least, the third strand was represented by

aesthetically refined poetry of Ivan Gundulić and Junije

Palmotić from Dubrovnik. Both writers explored stylistic

nuances and expanded Croatian vocabulary. During this period

(and frequently until 1850s) the ubiquitous name for Croatian

language was Illyrian (or “Slovinski”) because

Croats settled in the lands of Roman Illyricum and the Zeitgeist

preferred “classical” designations; also, not infrequently,

regional names (Bosnian, Dalmatian, Slavonian) had been used.This

"triple achievement" of Baroque

Slavism in first half of the 17th century laid the firm

foundation upon which later Illyrian movement (1830-1850)

completed the work of language standardization.

Ivan

Gundulić: Suze sina razmetnoga/Tears of the prodigal son, 1622

-

The

entire process described above can be best summarized in Croatian

linguist Dalibor Brozović's words: The Croatian language

has evolved towards its goal throughout its history. Glagolitic

and Cyrillic works were composed in the Latin script, but there

are no reverse cases. Kajkavian and Čakavian writers wrote in

Štokavian, but the reverse is unknown. The Štokavians who were

not neo-Štokavians accepted the neo-Štokavian basis, but not

the converse. The Ikavians wrote in Ijekavian, but not the other

way around. The natural result is Croatian standard language,

based on neo-Štokavian Ijekavian (što-ije) dialect and written

in the Latin script.

1700

to 1900

Expansion

of the Štokavian vernacular influence

Illyrian

movement, final scriptory reform and language unification

-

Through

the major part of the 18th century two seemingly contradictory

processes had been under way: envigoration of literary activity

in two Croatian dialects, Kajkavian (in the north-western

part of Croatia) and Štokavian (in the rest of Croatia and

in Bosnia); also, penetration of Štokavian influence on

Kajkavian writers and local idiom. However, political and

demographic factors again played the pivotal role: since

the major parts of contemporary Croatia (Slavonia and Dalmatia)

were liberated from Ottomans at the end of 17th century,

these areas, where Štokavian dialect predominated, became

centres of vigorous literary activity, mainly in the spirit

of dominant Enlightenment and nascent Sentimentalism. Two

enormously popular authors, a military officer from Slavonia

Matija

Relković and Dalmatian Fransciscan friar Andrija Kačić

Miošić, became a sort of cult writers in the 18th century:

their works, steeped in didacticism, folk wisdom and glorification

of heroic (frequently imaginary) epic past, although cannot

be, on aesthetic level, compared to best Croatian writing

in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, played crucial role

in the spread of neo-Štokavian dialect. They, along

with numerous other writers and lexicographers from Slavonia,

Dalmatia and Bosnia (although still under Turkish rule, Croats

in Bosnia and Herzegovina were ecclesiastically united with

their compatriots in Slavonia and Dalmatia in one Franciscan

province, Bosnia Argentina) set the scene for incipient «Illyrians»:

the Baroque Slavism had created ornate and expressive

idiom, but it was Kačić Miošić who, in his «Razgovor...»/»Discourse...»

produced the summa of Croatian folk mythologies, integrated

images of heroic, one might say Homeric past with the mundane

purpose of Christian propaganda and gave to the Croatian people

the first truly national book, unsurpassable bestseller that

crossed regional, dialectal and class boundaries.

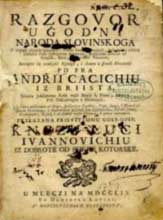

Andrija

Kačić Miošić: Razgovor ugodni naroda slovinskoga/Pleasant Discourse

of the Slovin people, 1756

-

The Illyrian movement, 1830-1850, centred in Croatia's

capital Zagreb (where Kajkavian dialect predominated)

and lead by Ljudevit Gaj, accomplished final cultural

unification of Croatian people. This movement, also called

Croatian national revival, was one among many similar

European movements in the «spring of nations» following

the period of Napoleonic wars. In the case of Croatian

revival, it was also the continuation of Ritter-Vitezović's

scriptory reform and ideological pan-Croatism and Kačić

Miošić's glorification of epic past, celebrated in verses

paradigmatic of neo-Štokavian idiom. Its results

in the field of language and linguistics can be summarized

thus: «Illyrians» had given the final form of Croatian Latin

script by adopting Czech and Polish diacritical marks and

inventing a few exclusively Croatian graphemes and, by opting

for the most widespread dialect among the Croats, Štokavian,

had unified all Croats in one Croatian literary koine.

Moreover, motivated by nuanced and far-sighted cultural

politics, Illyrian central figures (politician and philologist

Ljudevit Gaj, lexicographer, poet and politician

Ivan Mažuranić, writer and polymath Ivan Kukuljević

and philologist Vjekoslav Babukić) chose što-ije

dialect as the basis of Croatian koine,

instead of što-i, the native language-dialect of

the majority of Croats. The reasons for such a decision

were:

-

the

literature written in što-ije dialect, from 1500s

on, has been the richest among Croatian regional literatures

(and in many ways «older» than other, recently more developed

«antagonist» literatures like German: of course, no Croatian

poet of the time could «compete» with Goethe or Novalis)

and could be used as the strong shield against German and

Hungarian language «imperialism»- in the climate of Romanticism,

the claims of «antiquity» of a national literature were

particularly important. The «Illyrians» have, by adopting

and further developing što-ije dialect and by elevating

it to the status of Croatian official language (so far as

circumstances in Habsburg Empire permitted) effectively

halted Germanization (and other possible de-Croatization

programs).

-

The

«Illyrians» worked in the climate of romantic Pan-Slavism

that viewed all South Slavic languages as offshoots of one,

«Illyrian language». Since Serbs, the geographically

closest «Illyrian tribe», spoke što-e and što-ije

dialects, and Croats što-i and što-ije

dialects, the only possible «intersection» was što-ije

dialect. However, the history's final verdict was ironic:

Serbs, who didn't have a cultural tradition in što-ije

dialect abandoned it for standard language based on

more popular and widespread što-e dialect. On the

other hand, post-medieval Croatian cultural and linguistic

identity, formed in the 16th and 17th centuries, definitely

crystallized around što-ije based standard language.

«Illyrian» and South Slavic illusions of linguistic unity

of South Slavs had not passed the reality check.

-

The

Illyrian movement and its successor, the Zagreb philological

school, have been particularly successful in creating

the corpus of Croatian terminology that covered virtually

all areas of modern civilization. In short- they extended

and systematized the purist tendencies already present

in the by then more than 400 years old Croatian vernacular

literature and lexicography. This was especially visible

in two fundamental works: Ivan Mažuranić's and Josip

Užarević's:"German-Croatian dictionary" from 1842 and

Bogoslav Šulek's "German-Croatian-Italian dictionary

of scientific terminology", 1875. These works, particularly

Šulek's, systematized (ie., collected from older

dictionaries), invented and coined Croatian terminology

for the 19th century jurisprudence, military schools, exact

and social sciences, as well as numerous other fields (technology

and commodities of urban civilization). So, the “Illyrians”

assimilated and expanded central Croatian linguistic traits:

strong loyalty and respect towards Croatian literary and

philological heritage combined with linguistic purism and

word-coinage. The only field where “Illyrians” partially

failed was orthography: they, contrary to the tradition

of mainly phonemic Croatian orthography (from 1200s on),

which is best suited for a “transparent” language like Croatian

(or Latin, Spanish or Italian) adopted, in the spirit

of pan-Slavism, predominantly morphonological orthography

(better suited for “intransparent” languages like Czech

or Polish). But, this was a minor setback (later corrected

by orthographic manual authored by Ivan Broz in 1892)

compared to their triumphs in the vital areas of scriptory

unification, definite language standardization based on

što-ije dialect and continuation and extension of

dominant tendencies embedded in Croatian literary and linguistic

tradition.

Bogoslav

Šulek: Rječnik znanstvenoga nazivlja/ Croatian-German-Italian

dictionary of scientific terminology, 1875

-

The

19th century language development overlapped with the upheavals

that befell Serbian language. It was Vuk Stefanović Karadžić,

an energetic and resourceful Serbian language and culture

reformer, whose scriptory and orthographic stylization of

Serbian Cyrillic script and reliance on folk idiom made

a radical break with the past; until his activity in the

first half of the 19th century, Serbs had been using Serbian

variant of Church Slavonic and hybrid Russian-Slavonic language.

His “Serbian Dictionary”, published in Vienna 1818 (along

with the appended grammar), was the single most significant

work of Serbian literary culture that shaped the profile

of Serbian language (and, the first Serbian dictionary and

grammar until then). Karadžić chose što-ije dialect

as the basis for emerging Serbian standard language (although

virtually all works (covering the fields of literature,

lexicography and philology) written in što-ije dialect

in 350 years preceding his reforms belonged to the Croatian

culture and were, logically, considered by eminent

contemporary Serbian scholars as something alien and non-Serb)

because, as a folklorist, he was impressed by the folk poetry

idiom (Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian Muslim) expressed in

što-ije dialect. Although the majority of Karadžić's

reforms triumphed among Serbs after a struggle that lasted

more than 5 decades- his choice of što-ije dialect

as the basis for standard Serbian was largely abandoned.

A small part of Serbs still uses što-ije based Serbian

literary language, but the “variant” based on što-e

is vastly predominant among Serbs. Karadžić's work was the

revolution for Serbs; yet his influence on Croatian language

was only one of the reforms, mostly in some aspects of grammar

and orthography since the majority of his innovations had

been present in Croatian literary and linguistic corpora

for centuries.

-

But-

now has begun the process that entangled Croats and Serbs

in the unstable situation of two nations sharing virtually

the same language according to genetic linguistics- but

having frequently divergent political aims. Due to the fact

that both languages shared the common basis of South Slavic

neo-Štokavian dialect, they interfered in many normative

issues, particularly in orthography, phonetics, syntax and

semantics. On one hand, there was Serbian language,

based upon rustic folk idiom and, as it were, “untainted”

by history in the time of its “official” birth in the mid-1800s.

On the other side stood Croatian language, moulded

by more than 4 centuries old Croatian vernacular literature

in all three dialects- a language steeped in history; also,

a language formally shaped by linguists and writers very

conscious of deceptions of the past and wary of idealization

of purely folklore-based standard language. The situation

of two nations with similar and mutually intelligible, but

different languages (not unlike Bulgarian-Macedonian,

Hindi-Urdu, Malay-Bahasa Indonesian, Czech-Slovak

“pairs”) frequently led to polemics where language was used

as a political tool in ethno-territorial disputes. However,

in the 19th century will for cooperation dominated

over language squabbles: following the incentive of Austrian

bureaucracy which preferred some kind of "unified" Croatian

and Serbian languages for purely practical administrative

reasons, Slovene philologist Franc Miklošič (the

Habsburg crown man of confidence) initiated a meeting of

two Serbian philologists (including Vuk Karadžić)

and writers together with five Croatian "men of letters"

(Ivan Kukuljević and Ivan Mažuranić among

them). This, so-called "Vienna agreement" in 1850,

on the basic features of unified "Croatian or Serbian"

or "Serbo-Croatian" language was signed by all eight

participants (including Miklošič), but did not have any

effect in practice. Essentially, a more "unified" standard

appeared at the end of 19th century with

Croatian sympathizers of Vuk Karadžić, so called

"Croatian Vukovians", who wrote first modern (from

the vantage point of dominating neo-grammarian linguistic

school) grammars, orthographies and dictionaries of language

they called "Croatian or Serbian" (Serbs preferred

Serbo-Croatian). The key works were: the crucial

orthographic manual based on phonemic principle (in accordance

with Renaissance and Baroque Croatian writing, but differing

from mainly morphonological, Czech language-based orthography

preferred by “Illyrians”) by Ivan Broz (1892), monumental

grammar authored by preeminent fin de siecle Croatian linguist

Tomislav Maretić (1899) and dictionary by Broz

and Iveković (1901). These books temporarily fixed

the elastic (grammatically, syntactically, lexically) standard

of this hybrid language. However, the linguistic prescriptions

of this school in many areas ignored multicentenary Croatian

literary and philological tradition (mainly in the fields

of vocabulary and linguistic purism), so only those rules

that have had roots in the literary canon were accepted;

others have been ignored by modernist avant guarde writers

and “officially” abandoned by later linguists influenced

by French structuralism of de Saussure and Prague school

of Jakobson and Trubetzkoy. Needless to say, the colloquial

language remained generally unaffected by such nuances.

1900

to the present

Language

and politics

Birth

and death of Yugoslav supra-national program

-

But,

due to the fact that these two languages have had a radically

different past of almost four hundred years and only a few

decades of moderately peaceful convergence- it was inevitable

that they should eventually diverge. The Croatian good will

quickly evaporated in Serbian-dominated Yugoslavia

(1918-1941), when political pressures were applied to forge

them into one, Serbian-based language- all in the spirit

of supra-national Yugoslav ideology which had had roots

in the 19th century idealization of South Slavic «unity»,

but has mutated into a variant of Greater Serbian expansionist

program. This kind of «language planning», ie. forced Serbianization

of language in Croatia and Bosnia, was especially ruthless

in 1920s and 1930s, when Serbian language characteristics

(lexical, syntactical, orthographical and morphological)

had been officially prescribed for Croatian textbooks and

general communication. Also, this artificial "unification"

into one, Serbo-Croatian language was preferred by

neo-grammarian Croatian linguists (the most notable example

was influential philologist and translator Tomislav Maretić).

The recipe was simple: if a term is described by two words

in Croatian (a neologism and Greek/Latin Europeanism) and

one word in Serbian (Europeanism)- the "choice" was to suppress

Croatian neologism and "promote" Europeanism. For instance,

"geography" is "geografija" in Serbian, and "zemljopis"

and "geografija" in Croatian. The policy was to try

to establish "geografija" as the norm and to eliminate "zemljopis".

However, this school was virtually extinct by late 1920s

and since then leading Croatian linguists (Petar Skok,

Stjepan Ivšić and Petar Guberina) have been

unanimous in re-affirmation of Croatian purist tradition.

The situation somewhat eased in the eve of World War 2,

but with the capitulation of Yugoslavia and creation of

Nazi-Fascist puppet «Independent State of Croatia» (1941-1945)

came another, this time hardly predictable and extremely

grotesque attack on standard Croatian: totalitarian dictatorship

of Ante

Pavelić pushed natural Croatian purist tendencies

to ludicrous extremes and tried to reimpose older morphonological

orthography preceding Broz's prescriptions from 1892.

But, Croatian linguists and writers were strongly opposed

to this travesty of “language planning”- in the same way

they rejected pro-Serbian forced unification in monarchist

Yugoslavia (1918-1941). Not surprisingly, no Croatian

dictionaries or Croatian

grammars had been published during this period.

-

While during monarchist Yugoslavia

"Serbo-Croatian" unification was motivated mainly by Greater

Serbia policy, in the Communist period (1945 to 1990)

it was the by-product of Communist

centralism and "internationalism". Whatever the intentions,

the result was the same: the suppression of basic features

that differ Croatian language from Serbian language-from

orthography to vocabulary. No Croatian

dictionaries (apart from historical "Croatian or Serbian",

conceived in the 19th century) appeared until 1985,

when Communist centralism was well in the process of decay.

In Communist Yugoslavia, Serbian

language and terminology were "official" in a few areas:

the military, diplomacy, Federal Yugoslav institutions (various

institutes and research centres), state media and jurisprudence

at Yugoslav level; also, the language in Bosnia

and Herzegovina was gradually Serbianized in all levels

of educational system and the republic's administration.

Serbian linguistic imperialism was encouraged by the Communist

Party-State, which had replaced the Western concept of Nation-State

in the Communist countries or the Eastern Byzantine concept

of the Church-State with its Messianic politico-religious

Orthodoxy. Notwithstanding the declaration of intent of

AVNOJ (The Antifascist Council for the National Liberation

of Yugoslavia) in 1944, which proclaimed the equality of

all languages of Yugoslavia (Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian

and Macedonian)-everything had, in practice, been geared

towards the supremacy of the Serbian language. This was

done under the pretext of "mutual enrichment" and "togetherness",

hoping that the transient phase of relatively peaceful life

among peoples in Yugoslavia would eventually give way to

one of fusion into the supra-national, essentially paradoxical

"Yugoslav" nation and provide a firmer basis for Serbianization

to be stepped up. However- this "supra-national engineering"

was doomed from the outset: the nations that formed ephemeral

Yugoslav state were formed long before its incipience and

all unification pressures only poisoned and exacerbaced

inter-ethnic/national relations.

-

After

World War II, Yugoslavia was established as a federation.

In the 1950s, a hundred years after the Vienna Agreement

whose aim was to establish the Serbo-Croatian language,

the differences between the Croatian and Serbian literary

languages had not lessened. They were the result of several

contrasting factors

-

Croatian

vs. Serbian literary tradition

-

Latin

vs. Cyrillic script

-

Ijekavian

variant of Štokavian as the basis for the Croatian literary

language vs. Ekavian variant of Štokavian as

the basis for the Serbian literary language

-

Broz/Boranić's

orthography for the Croats vs. Belić's orthography for the

Serbs

-

Croatian

technical and scientific terms vs. Serbian technical and

scientific terms

-

Croatian religious and philosophical heritage and terminology

vs. Serbian religious and philosophical heritage and terminology.

-

Croatian language structural characteristics vs. Serbian

language structural characteristics (phonetics, phonology,

morphology, syntax, semantics)

The

single most important effort by ruling Yugoslav Communist elite

to erase the "differences" between two languages and in practice

impose Serbian Ekavian language, written in Latin script, as the

"official" language of Yugoslavia is the so called Novi Sad

Agreement. Twenty five Serbian, Croatian and Montenegrin philologists

came together in 1954 to sign the Novi Sad Agreement (named after

the town of this event). A common Serbo-Croatian or Croato-Serbian

orthography was compiled in an atmosphere of state repression

and fear. There were 18 Serbs and 7 Croats in Novi Sad. The «Agreement»

was seen by the Croats as a defeat for the Croatian cultural heritage.

According to the eminent Croatian linguist Ljudevit Jonke,

it was imposed on the Croats. The conclusions were formulated

according to goals which had been set in advance, and discussion

had no role whatsoever. In more than a decade to follow the principles

of Novi Sad Agreement were put into practice.

A

collective Croatian reaction against such de facto Serbian imposition

erupted on 15th March 1967. On that day, nineteen Croatian scholarly

institutions and cultural organizations dealing with language

and literature (Croatian Universities and Academy),

including foremost Croatian writers and linguists (Miroslav

Krleža, Radoslav Katičić, Dalibor Brozović and Tomislav

Ladan among them) issued the "Declaration Concerning the

Name and the Status of the Croatian Literary Language". In

the Declaration, they asked for amendment to the Constitution

expressing two claims:

-

the equality not of three but of four literary languages,

Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and Macedonian,

and consequently, the publication of all federal laws and

other federal acts in four instead of three languages

-

the use of the Croatian standard language in schools and all

mass communication media pertaining to the Republic of Croatia.

The Declaration accused the federal authorities in Belgrade

of imposing Serbian as the official state language and downgrading

Croatian to the level of a local dialect.

Notwithstanding

the fact that "Declaration" was vociferously condemned

by Yugoslav Communist authorities as an outburst of "Croatian

nationalism"-Serbo-Croatian forced unification was essentially

halted and the uneasy status quo remained until the end of Communism.

The sterility of Yugoslav ideology and its detrimental effects

on linguistic culture can be best exemplified by scarcity of

Croatian dictionaries, grammars and other works that had

appeared from 1920 to 1980- and the marginalization or prohibition

of those works (especially studies in sociolinguistics and phonology,

orthographic manuals and grammars) that were written from the

vantage point of modern linguistic theories. The Serbo-Croatian

«unity» could be preserved only by reliance on dated philological

schools that belonged properly to the 19th century. Also, when

compared to earlier periods- both quantity and quality of Croatian

language works officially allowed by the regime heavily lagged

behind those published in the 17th, 18th or 19th centuries.

-

In the decade between the death of Yugoslav dictator Tito

(1980) and the final collapse of Communism and Yugoslavia

(1990/1991), major works that manifested irrepressibility

of Croatian linguistic culture had appeared. The studies of

Brozović, Katičić and Babić that had

been circulating among specialists or printed in the obscure

philological publications in the 60s and 70s (frequently condemned

and suppressed by Communist authorities) have finally, in

the climate of dissolving authoritarianism, been published

in the broad daylight. This was formal «divorce» of Croatian

language from Serbian (and, strictly linguistically speaking,

death of Serbo-Croatian). The works, based on modern

fields and theories (structuralist linguistics and phonology,

comparative-historical linguistics and lexicology, transformational

grammar and areal linguistics) revised or discarded older

«language histories», restored the continuity of Croatian

language by definitely reintegrating and asserting specific

Croatian language characteristics (phonetic, morphological,

syntactic and lexical) that had been constantly suppressed

in both Yugoslav states and finally gave modern linguistic

description and prescription of Croatian language. Among

many monographs and serious studies, one could point out to

works issued by Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, particularly

Katičić's «Syntax» and Babić's «Word-formation».

Radoslav

Katičić: Sintaksa hrvatskoga književnoga jezika/Syntax of Croatian

Literary Language, 1986

Stjepan

Babić: Tvorba riječi u hrvatskom književnom jeziku/Word-formation

in Croatian Literary Language, 1986

-

After the collapse of Communism and the birth of Croatian

independence (1991), situation with regard to the Croatian

language has become stabilized. Finally freed from political

pressures and de-Croatization impositions, Croatian linguists

expanded the work on various ambitious programs and intensified

their studies on current dominant areas of linguistics: mathematical

and corpus linguistics, textology, psycholinguistics, language

acquisition and historical lexicography. From 1991

numerous representative Croatian linguistic works were published,

among them four voluminous monolingual dictionaries of contemporary

Croatian, various specialized dictionaries and normative manuals

(the most representative being the issue of Institute for

Croatian Language and Linguistics). For a curious bystander,

probably the most noticeable language feature in Croatian

society was re-Croatization of Croatian language in all areas,

from phonetics to semantics- and most evidently in everyday

vocabulary. Some observers with Yugoslav affinities deplored

such a course of events. But, having in mind the vocal silence

of such “multiculturalist” proponents of Serbo-Croatian

when Croatian orthographies were literally burnt in auto-da-fes

(1971), one can only conclude with regard to the death of

this “language”: qualis vita, et mors ita !

Jure

Šonje (ured./edit.): Rječnik hrvatskoga jezika/Croatian Dictionary,

2000

Institut

za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje: Hrvatski jezični savjetnik,

1999

Institute

for Croatian Language and Linguistics: Croatian Language Counsellor,

1999

Ivo

Banac: Main Trends in the Croatian Language Question, Yale University

Press, 1984

Branko

Franolić: A Historical Survey of Literary Croatian, Nouvelles

editions latines, Paris, 1984

Milan

Moguš: A History of the Croatian Language, Globus, Zagreb, 1995

Miro

Kačić: Croatian and Serbian: Delusions and Distortions, Novi Most,

Zagreb, 1997

Croatian

language history

Croatian

language from the eleventh century to the computer age

FOLIA

CROATICA-CANADIANA: A magnificent 243 pages (3.4 Mb)

long

survey on all aspects of Croatian language history. Slow download.

Representative

texts in Croatian

A

COMPENDIUM OF CROATIAN LITERARY RESOURCES ON THE WEB

A

digital collection of poetry dating from the Renaissance to the

end of the 19th century

The

major Croatian works from the Renaissance to the early Modernism

Silvije

Strahimir Kranjčević: collected works

Tin

Ujević- selected poetry

Miroslav

Krleža- selected prose, short stories and a novel

Mak

Dizdar- selected poetry

Bible

in Croatian (searchable text)

Croatian

standard language

Croatian

language: introduction, pronunciation and basic phrases

Croatian

National Corpus

Institutions

Old

Church Slavonic Institute

Croatian

Academy of Arts and Sciences: The Department od Philological Sciences

Institute

for Croatian Language and Linguistics

Zagreb

University, Faculty of Philosophy: Croatian Department

Lexicographic

Institute Miroslav Krleža

Matica

hrvatska

Croatian Old Dictionary Portal

|