Web catalog

Most read

Most read last 7 days

Most Discussed

Top rated

Statistics

- Total registered users: 10061

- Total articles: 23656

- Total comments: 2087

- Last entry: Kebo presenting evidence that Izetbegovic brought mujahideen to Bosnia

- Last update: 11.01.2019. 23:44

1500 to 1700 Modern Croatian language Turkish invasion and migrations Renaissance and Baroque regional literatures and standardization

Written 03.12.2009. 12:02

During 16th and 17th centuries occurred many processes that shaped the profile of future Croatian standard language: the Ottoman invasion and permanent warfare, followed by mass depopulation and migrations have had at least four lasting consequences:

During 16th and 17th centuries occurred many processes that shaped the profile of future Croatian standard language: the Ottoman invasion and permanent warfare, followed by mass depopulation and migrations have had at least four lasting consequences:the area of Čakavian, the oldest Croatian dialect was greatly narrowed. Although the Renaissance literature in Čakavian vernacular achieved remarkable triumphs (epic and lyric poetry, novel) in the 16th century (especially on islands Hvar and Korčula and cities Split and Zadar, with key authors like Marko Marulić, Hanibal Lucić and Petar Zoranić), its demographic and cultural basis had soon become exhausted and Čakavian lost the chance to become the basis of Croatian national language.

Turkish conquests have been followed by migrations of Vlachs- mainly Slavicized shepherding paleo-Balkans populace from earlier conquered areas in Albania, Serbia, Montenegro and Herzegovina. The result was expansion of neo-Štokavian dialect in Ikavian (što-i) and Ijekavian (što-ije) forms. The majority of settlers later nationally identified according to the faith they professed: the Eastern Orthodox Vlachs became Serbs and Roman Catholics became Croats.

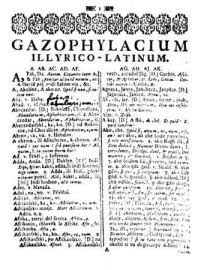

The literature and lexicography in Kajkavian dialect appeared on the scene, but the most influential and promising was the literature in Čakavian-Kajkavian-Štokavian interdialect, based in central Croatia and supported by powerful Croatian nobles Zrinski and Frankopan (both writers themselves). However, this extraordinary activity that produced at least two major figures: polymath, forerunner of modern Croatian national ideology and script reformer Pavao Ritter-Vitezović and lexicographer Ivan Belostenec (his magnum opus, the 2,000 pages long Kajkavian-based interdialectal dictionary “Gazophylacium” (ca. 1670) was published some 60 years after its completion) was cut short by execution of Zrinski and Frankopan in Bečko Novo Mesto 1671, after a kangaroo trial orchestrated by the Vienna court-leaving Croatia literally decapitated for a time. The Kajkavian-based interdialect later flourished in north-western Croatia (in and around Zagreb), but was essentially confined to a corner of Croatian language area and could not become transregional Croatian koine.

the extraordinary flourishing and continuous influence of the southern Croatian Renaissance literature in Dalmatia, with centres in cities like Split, Zadar and Dubrovnik, or islands Korčula and Hvar, laid the foundation for the idiom that was to became the basis of Croatian standard language. At first, it was written in Čakavian and Štokavian dialects (with strong dialectal interference, so that many features of Čakavian can be found in Štokavian and vice versa), but soon, after the depopulation and economic and cultural marginalization of other Dalmatian towns, the Dubrovnik writers, who wrote in increasingly unidialectal Štokavian-Ijekavian, remained alone on the scene. The key authors are poets Šiško and Vladislav Menčetić, Dominko Zlatarić, numerous poets from Ranjina\'s collection of sonnets and the dramatist Marin Držić.

http://aatseel.org/croatlit/croataatseel2.htm

A COMPENDIUM OF CROATIAN LITERARY RESOURCES ON THE WEB

A digital collection of poetry dating from the Renaissance to the end of the 19th century

What the Renaissance writers accomplished in the 16th century had been further developed and refined in the 17th. This period, sometimes called Baroque Slavism was crucial in formation of literary idiom that was to become Croatian standard language: the 17th century witnessed luxuriance in three fields that shaped modern Croatian:

The first one was represented by the linguistic works of Jesuit philologists Kašić and Mikalja: the first Croatian grammar, authored by Bartol Kašić under the title: “Institutionum linguae illyricae libri duo”, appeared in Rome 1604. Interestingly enough, the language of Jesuit Kašić\'s unpublished (until 2000) translation of the Bible (Old and New Testament, 1622-1636) in the Croatian Štokavian-Ijekavian dialect (the ornate style of the Dubrovnik Renaissance literature) is as close to the contemporary standard Croatian language (problems of orthography apart) as are French of Montaigne\'s “Essays” or King James Bible English to their respective successors - modern standard languages. The richness of Kašić\'s translation can be seen in the vocabulary: while the original Old Testament consists of 8,674 Hebrew words, and New Testament of 5,624 Greek words, the vocabulary of Kašić\'s Bible translation numbers near 20,000 words. However, Kašić\'s most influential book was “Ritual Rimski”/The Roman Ritual, a liturgical compendium that had been in use from 1640 to 1929 and has decisevely shaped the profile of Croatian language; Mikalja\'s “Thesaurus linguae Illyricae” was first respectable (25,000 Croatian entries) dictionary of Croatian language mainly in Štokavian-Ijekavian idiom.

another strong influence was the energetic literary activity of Bosnian Franciscan Matija Divković, whose Counter-Reformation writings (popular tales from the Bible, sermons and polemics) were widespread among Croats both in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and played the crucial role in preserving and forging the cultural and linguistic unity among Croatian common people who lived in two empires: Ottoman and Habsburg.

and, last but not least, the third strand was represented by aesthetically refined poetry of Ivan Gundulić and Junije Palmotić from Dubrovnik. Both writers explored stylistic nuances and expanded Croatian vocabulary. During this period (and frequently until 1850s) the ubiquitous name for Croatian language was Illyrian (or “Slovinski”) because Croats settled in the lands of Roman Illyricum and the Zeitgeist preferred “classical” designations; also, not infrequently, regional names (Bosnian, Dalmatian, Slavonian) had been used.This "triple achievement" of Baroque Slavism in first half of the 17th century laid the firm foundation upon which later Illyrian movement (1830-1850) completed the work of language standardization.

The entire process described above can be best summarized in Croatian linguist Dalibor Brozović\'s words: The Croatian language has evolved towards its goal throughout its history. Glagolitic and Cyrillic works were composed in the Latin script, but there are no reverse cases. Kajkavian and Čakavian writers wrote in Štokavian, but the reverse is unknown. The Štokavians who were not neo-Štokavians accepted the neo-Štokavian basis, but not the converse. The Ikavians wrote in Ijekavian, but not the other way around. The natural result is Croatian standard language, based on neo-Štokavian Ijekavian (što-ije) dialect and written in the Latin script.

Related articles

- 1900 to the present Language and politics Birth and death of Yugoslav supra-national program

- 1700 to 1900 Expansion of the Štokavian vernacular influence Illyrian movement, final scriptory reform and language unification

- 1100 to 1500 Church Slavonic literature, dialectal differentiation and vernacular literacy Cyrillic and Latin Script

- History: 600 to 1100 Latin and Church Slavonic literacy Glagolitic Script as the medium of Croatian Church Slavonic

- Pre-history: Indo-European and Slavic languages

- Archive of related articles

Kontaktirajte nas

Kontaktirajte nas

No comments