In the first stage of the Croatian nation-state and the Croatian policy formation, there was a 100% possessiveness towards Bosnia: Bosnia was ours completely. The possessiveness was based on ethnogenesis: Muslims are Croats of Islamic religion, because they are of Croatian origin, and Serbs are either Croatian members of the Orthodox Church, or unwanted newcomers whom the possessiveness does not recognize as a participating factor...

In the dynastic crisis and the wars that followed the death of King Louis I Angevin in 1382, the Croatian nobility played the leading role. Nevertheless, the members of the Croatian nobility did not have enough power to turn that crisis to their own advantage by supporting a king of their own choice to mount the throne.

Reaching back today to the historical right of claiming a country or an area of land, in any form of historical discourse, not only seems undesirable in contemporary terms, but in some circles, the subject often becomes a laughing matter.

April 7th, 1992.

By the decision of its President, Dr. Franjo Tudjman, Republic of Croatia was among the first countries in the world to recognize the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina, its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Croats (and Serbs) remember many cruel and demeaning acts perpetrated by the Muslims, who acted as the protected privileged caste. These include many pogroms and murders of Franciscans, as well as the sale of Croats into slavery.

Up until the 19th century, historical sources claim that Bosniaks of all three faiths (Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims) live in Bosnia.

The Ottoman invasion was unleashed towards Bosnia, but Bosnian aristocrats at the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century, such as Hrvoje Vukcic Hrvatinic and Stjepan Kosaca, were almost solely preoccupied with their parochial power games and preservation of influence spheres.

Since there were no adherents of the Orthodox faith in Bosnia before the arrival of the Ottomans, it can be concluded that the direct descendants of the indigenous population are today's Croats and Bosniaks-Muslims. One of the facts that proves this is the use of the "ikavica" sub-dialect by both national groups.

Medieval Bosnia shared many characteristics with other South-Slavic states of the period. That political domain (not a state!) was established as a military commonwealth and functioned as a patriarchal family.

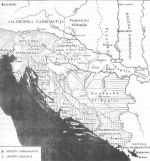

When Bosnia fell to the Ottomans in 1463, and the subsequent process of Islamisation that ensued, was a key historical turning point. Now a part of the Ottoman Empire, Bosnia still remained a border region as far as Croatian history was concerned.

In evaluating the role of the Franciscan order in medieval Bosnia, the fact that the western church had an earlier presence in Bosnia, a long time before the arrival of the Franciscans, shouldn\\\'t be ignored. As was pointed out earlier, the heretical "Bosnian church" itself grew out of the Bosnian Catholic diocese.

Alongside the narrow definition of a Bosnian contained in the Cyrillic documents, in Latin sources from the 14th and 15th Century about medieval Bosnia, a more broad application of the Bosnian name is used. Firstly in Latin scripts about the heretic "Bosnian church".

No Bosnian documents from the late 13th and early 14th Century have survived. Ethno-social occurrences from that time period thus stay outside a historian's view, but at the time when Bosnia, under Ban Stjepan II Kotromanic entered a phase of territorial expansion and social growth, the concepts of national consciousness became more complex and with new factors added to the mix.

Such unusual use of the terms "Srblin" and "Vlah" between the Serbian, Bosnian and Dubrovnik public offices indicates that it could only occur in Bosnia because it's ethno-social order and a national name was still under development in the first half of the 13th Century. National characteristics of the Slavs in Bosnia had not clearly developed by this time.

Research on ethno-social development of Bosnia runs into difficulties even during the translation of Bosnian Cyrillic documents from the 13th Century, especially in three documents attributed to Ban Matej Ninoslav. In these, Matej Ninoslav uses the term "Srblin" (Serb) for inhabitants of Bosnia and juxtaposes it with "Vlah" (Vlach) for the inhabitants of Dubrovnik.50 These designations have been subject to many interpretations, ranging from complete rejection to absolute acceptance.51 In order to explain this historical enigma, it is necessary to analyze Cyrillic documents from the 12th and 13th Centuries.

Kontaktirajte nas

Kontaktirajte nas