When Bosnia fell to the Ottomans in 1463, and the subsequent process of Islamisation that ensued, was a key historical turning point. Now a part of the Ottoman Empire, Bosnia still remained a border region as far as Croatian history was concerned.

In evaluating the role of the Franciscan order in medieval Bosnia, the fact that the western church had an earlier presence in Bosnia, a long time before the arrival of the Franciscans, shouldn\\\'t be ignored. As was pointed out earlier, the heretical "Bosnian church" itself grew out of the Bosnian Catholic diocese.

Alongside the narrow definition of a Bosnian contained in the Cyrillic documents, in Latin sources from the 14th and 15th Century about medieval Bosnia, a more broad application of the Bosnian name is used. Firstly in Latin scripts about the heretic "Bosnian church".

No Bosnian documents from the late 13th and early 14th Century have survived. Ethno-social occurrences from that time period thus stay outside a historian's view, but at the time when Bosnia, under Ban Stjepan II Kotromanic entered a phase of territorial expansion and social growth, the concepts of national consciousness became more complex and with new factors added to the mix.

Such unusual use of the terms "Srblin" and "Vlah" between the Serbian, Bosnian and Dubrovnik public offices indicates that it could only occur in Bosnia because it's ethno-social order and a national name was still under development in the first half of the 13th Century. National characteristics of the Slavs in Bosnia had not clearly developed by this time.

Research on ethno-social development of Bosnia runs into difficulties even during the translation of Bosnian Cyrillic documents from the 13th Century, especially in three documents attributed to Ban Matej Ninoslav. In these, Matej Ninoslav uses the term "Srblin" (Serb) for inhabitants of Bosnia and juxtaposes it with "Vlah" (Vlach) for the inhabitants of Dubrovnik.50 These designations have been subject to many interpretations, ranging from complete rejection to absolute acceptance.51 In order to explain this historical enigma, it is necessary to analyze Cyrillic documents from the 12th and 13th Centuries.

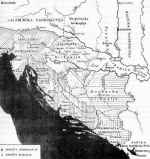

The breakout from the initial core ran parallel with the development of an independent Bosnian state. Bosnia had expanded past the midpoint of the river Drina, towards the Serb lands, perhaps as early as during the reign of Ban Kulin (towards the end of the 12th century), but definitely during the reign of Ban Matej Ninoslav (mid 13th century). Crucial for Bosnian development was its territorial drive towards west, south-west and further south to the coast, especially toward the eastern Adriatic coast, all these being Croatian regions. Further Bosnian territorial drives in 13th and 14th centuries, the annexation of parts of the Croatian kingdom (Donji Kraji and Zavrsje) had a twofold effect. First, Bosnia now included significant parts of the Croatian kingdom, and secondly, Bosnia was now in a close geopolitical and economic relationship with the surrounding Croatian lands.

The original Bosnia, or "small land of Bosnia" (to horion Bosona) was for the first time mentioned in the middle of the 10th century in the work of Constantine Porfirogenet (De administrando imperzo), as a part of Duke Caslav\'s Serbia, but however, clearly separated from Serbia proper.46 The original Bosnia was spread across the highlands around the upper stream of the river Bosna. It was separated from the neighbouring regions by a mountain range towards rivers Vrbas, Neretva and Drina. In order to develop, Bosnia had to expand territorially from its core.

Kontaktirajte nas

Kontaktirajte nas